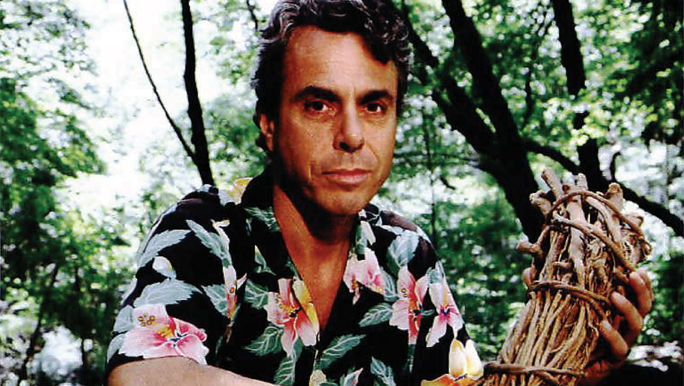

Medicine Hunter Chris Kilham, with Kava root. Photo by Sarah Claire Ahlers, for Psychology Today

Chris Kilham scours the earth for nature's most potent botanical drugs.

More than four billion people use plants as medicine. Chris Kilham wants that number higher. In his role as a medicine hunter, he travels to the planet's farthest regions, investigating nature's most potent botanical drugs and scoping ways for companies to bring them to market. And if he has to walk on some hot coals along the way, so be it. Although Kilham has no formal education in botany, he writes books (13 so far), appears on TV and radio programs, and lectures at the University of Massachusetts.

What do you learn on your trips?

I find out everything I can about the plant's role in the culture and its chain of trade so I can advise companies on how to acquire that plant material in ways that are sustainable and that help the people who do the real hard labor. If you can create market opportunity, then native people won't go off to the cities to become impoverished taxi drivers—and the land will be protected.

In the 1990s, you made a star out of the stress-relieving kava root. Any other favorite plants?

The adaptogens enhance your overall stamina, strength, and well-being. On the other side of the spirit veil, I spend more than a little bit of time researching the hallucinogens. I personally believe ayahuasca [a psychedelic Amazonian brew] is also the greatest natural healing agent, period.

Have you found yourself in dangerous situations?

The most hazardous are transportation- and hygiene-related. The worst one was a boat ride with some native guys down in the South Pacific that turned really ugly really fast. Fifteen-foot waves pounded the crap out of us. For a couple hours we thought we were dead men.

You were named an honorary chief in a village in Vanuatu.

I'm a white guy from the suburbs of Boston and I don't try to go native because that's an idiot's errand, but I go as far in as I'm allowed. I stay with these people and play with their kids and forage with them and walk on fire and kill pigs and cut papaya and whatever the hell has to happen. In terms of permanently moving to the outlands, that just depends on how lost the U.S. becomes in junk food, television, and pharmaceuticals. I still maintain hope.

How do other ethnobotanists see you?

If I have a unique position, it's that I'm equally comfortable in the world of media. I don't anticipate discovering the remedy nobody's ever found before. That's not my role. This one shaman—she was 103 years old—she said, "You bridge the worlds."